Writing with All Five Senses: Immersing Your Reader in the Scene

- rileytommy10

- Aug 2, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 4, 2025

By Tom Riley

Good writing tells a story. Great writing makes you feel it.

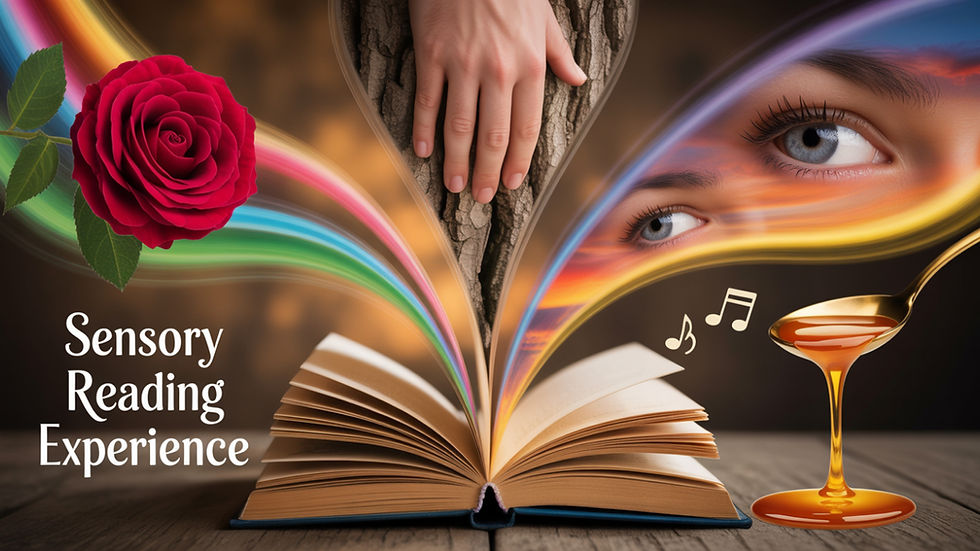

One of the most powerful tools in a writer’s arsenal is sensory detail — bringing a scene to life through sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. When you engage all five senses, you transform words on a page into a living, breathing experience your readers can step into.

We experience the world through all five senses. Smells can trigger deeply personal memories. Sounds can build anticipation. A single touch can ground us in a moment. Yet many new writers rely almost entirely on sight when shaping the world for their characters — forgetting that those characters should also hear, feel, smell, and taste the world around them.

By using all five senses effectively, you paint a vivid mental picture in the reader’s mind, transforming your narrative from something they watch to something they experience. Which sense you emphasize will depend on your setting, mood, and story needs.

Why Sensory Detail Matters

Have you ever read a story that made you feel you were standing right there in the moment? That magic often comes from sensory language. It allows readers to visualize, hear, smell, taste, and feel everything happening in a story, making the experience both immersive and memorable.

Sensory language works because our brains are wired to respond to it. A scent can instantly spark nostalgia. The texture of rough wood under fingertips can bring tangibility to an otherwise abstract moment. The sound of footsteps in a silent hallway can stir unease before a single threat appears.

When readers can see, hear, smell, taste, and touch your story world, they stop being observers and become active participants — emotionally connected to the characters and events.

Breaking It Down: The Five Senses in Action

Sight — The most frequently used sense in writing, but it should go beyond surface observation. Describe color, movement, light, and texture. Flat: The room was dark. Sensory-Rich: The room was thick with shadows, the air heavy with the scent of damp wood, and a slow drip echoed off the cold, uneven floor.

Sound — Ambient noise can set the mood, reveal tension, or hint at danger. Flat: It was noisy. Sensory-Rich: The air buzzed with overlapping conversations, the clink of glasses, and the sharp hiss of steam escaping from the kitchen.

Smell — Often overlooked, yet one of the most powerful triggers of memory and emotion. Flat: It smelled good. Sensory-Rich: The sweet aroma of warm cinnamon rolls curled through the air, wrapping around her like a childhood memory.

Taste — Perfect for food scenes, but also useful for atmosphere (“salt in the air,” “copper on the tongue”). Flat: The tea was bitter. Sensory-Rich: The tea was bitter, with a faint smokiness that lingered long after the first sip.

Touch — Texture, temperature, and sensation make the reader feel present. Flat: The wood was rough. Sensory-Rich: Her fingertips traced the weathered grooves, splinters catching at her skin.

Layering the Senses

One of the most effective ways to immerse readers is to layer sensory details. Start with a dominant sense — often sight — then weave in one or two others to create a more complete and multidimensional scene.

Example: Flat: The forest was quiet. Layered: The forest hummed with the soft rustle of leaves, the earthy scent of damp soil rising with each step, and the cool touch of mist brushing her skin.

This layering transforms a single-sense observation into a scene the reader can step into.

Metaphors, Similes, and Emotional Resonance

Metaphors and similes make sensory descriptions more relatable by connecting them to familiar experiences:

Her voice was smooth as velvet and rich like dark chocolate.

The heat wrapped around him like a heavy wool blanket.

Sensory details can also evoke emotion. A creaking floorboard might stir fear. The scent of rain might awaken longing. The roughness of a gravestone might bring grief into sharp focus. Every sensory choice should serve your story’s mood.

Flat vs. Sensory-Rich: Five Genre Examples

1. Mystery / Thriller Flat: The hallway was dark and quiet. Sensory-Rich: The hallway stretched ahead like a tunnel of ink, the stale air heavy with dust. Somewhere in the shadows, a faint drip echoed, each drop a metronome marking the seconds until something — someone — moved.

2. Romance Flat: She enjoyed the date. Sensory-Rich: The flicker of candlelight danced across his face, softening the sharp lines of his jaw. The air between them was warm with the scent of roses and melted wax, and every laugh she released seemed to linger like the taste of strawberry wine on her lips.

3. Fantasy Flat: The dragon was huge. Sensory-Rich: The dragon’s scales shimmered like molten gold under the noonday sun, each movement sending a ripple of heat into the air. Its breath smelled of scorched earth and charred bone, and when it roared, the ground trembled as though the world itself flinched.

4. Historical Fiction Flat: The market was busy. Sensory-Rich: The market thrummed with life — vendors shouting over one another, the smell of fresh-baked bread colliding with the tang of salted fish. The cobblestones were slick from an early rain, and children darted between stalls, their laughter rising above the din.

5. Literary Drama Flat: He was nervous. Sensory-Rich: Sweat pooled in the hollow of his back, dampening his shirt. His tongue stuck to the roof of his mouth, the taste of stale coffee lingering. Every sound in the room — the shuffle of papers, the squeak of a chair — felt magnified, crowding the silence between his heartbeat and his next breath.

Writing Exercises to Try

One Sense at a Time: Write a scene focusing on just one sense. Then rewrite it, adding others until all five are present.

Sensory Swap: Take a basic sentence (“The coffee was hot”) and rewrite it to engage at least three senses.

Memory Trigger: Think of a personal memory tied to a scent or sound. Write a scene inspired by it, letting that sensory cue guide the emotion.

Final Thought

Writing with all five senses is like turning a black-and-white sketch into a full-color painting. Sensory language is not just decoration — it’s the foundation for immersive storytelling.

So next time you write a scene, ask yourself:

What can my reader hear, smell, taste, or feel right now?

By weaving in sensory details, you create narratives that don’t just tell a story — they invite readers to live it.

Comments